Executive Functioning Challenges in Neurodivergent / Autistic Children and Adults

Autistic children and adults often experience differences in executive functioning (EF). Executive functioning includes the skills we use to plan, organise, manage emotions, shift attention, remember information, and get things done. These differences do not at all imply laziness, low ability, or lack of effort. They reflect real neurological differences that affect how autistic people experience daily life.

Executive functioning challenges can influence how autistic people connect with others, cope with environments, and manage everyday demands. When these challenges are not understood, they can easily be mistaken for behaviour problems or a lack of motivation.

This blog is written for caregivers, teachers, family members, friends, and peers, as well as for neurodivergent/autistic children and adults themselves. Its purpose is to support understanding, self-awareness, and the development of realistic, healthy routines. The overall aim is to reduce stress, enhance well-being, and foster meaningful connections with the outside world, particularly when feelings of disconnection are present.

The topic is explored across four key areas, as outlined below.

1. Understanding the Impact Across Neurological Areas

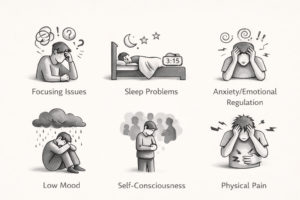

Executive functioning is made up of several connected brain processes. In autistic people, these processes may develop or work differently. Difficulties can include:

- Starting tasks or activities

- Holding information in mind, such as following several instructions

- Coping with change or switching between tasks

- Managing impulses, sensory overload, or strong emotional reactions

- Regulating emotions, such as anxiety, frustration, or shutdowns

These difficulties are often made harder by:

- Sensory sensitivity

- Overthinking increases the likelihood of cognitive distortions

- Ongoing anxiety or uncertainty

- Past experiences of being misunderstood, criticised, or overwhelmed

- Sleep problems or sleep disturbances can significantly reduce attention, emotional regulation, and mental energy

Sleep plays a crucial role in executive functioning. Poor or irregular sleep can make planning, focus, emotional control, and flexibility much harder the next day. Many autistic children and adults experience disrupted sleep due to sensory sensitivities, anxiety, or difficulties winding down.

Alongside sleep, basic self-care routines can strongly impact executive functioning. Support with sleep hygiene, regular meals, a balanced diet, gentle physical activity, and movement can all help stabilise energy levels, mood, and cognitive capacity. While these factors do not remove executive functioning differences, they can support day-to-day functioning and reduce overall strain.

Because these systems work together, a difficulty in one area can cascade into others. For many autistic people, ongoing anxiety or uncertainty can lead to avoidance when situations feel overwhelming or unsafe. While at first protective, over time, avoidance can reduce opportunities to practise everyday life skills and increase self-isolation. Confidence can drop, mood may be affected, and depression can develop.

Low self-confidence can also worsen, especially when autistic children do not feel understood by their caregivers or are unable to form meaningful connections with their peers. Repeated experiences of misunderstanding, rejection, or failure can strongly shape how a child sees themselves. These negative experiences may lead the child to stop trying, avoid social situations, and take fewer positive risks. This process is closely linked to what psychologist Martin Seligman described as Learned Helplessness, where a person learns to believe that their actions will not lead to positive change. When this happens, children and adults may practise life skills less, engage less in social relationships, and progressively withdraw, which can cause difficulties to deepen rather than improve.

Importantly, executive functioning changes day to day. An autistic child or adult may cope well in one setting, such as at home, but struggle much more in another, such as school, work, or social situations. This is often because the person has developed specific routines or patterns that help them feel safe and regulated in familiar environments. These routines can sometimes look like obsessive or compulsive behaviour from the outside, but they usually serve an important calming and organising function.

While these routines can support functioning and emotional safety at home, they may not transfer easily to less predictable environments. As a result, the gap between the familiar inner world and the demands of the outside world can grow. This can increase anxiety, avoidance, and feelings of disconnection, making it harder for the person to cope in new or changing situations.

2. How Executive Functioning Affects Daily Life

Executive functioning differences can strongly affect everyday activities. These difficulties are often invisible to others. Common examples include:

- Struggling to get started in the morning or move between activities

- Difficulty managing time, deadlines, or priorities

- Finding it hard to start or maintain friendships

- Avoiding new places or situations because they feel unpredictable

- Appearing withdrawn, resistant, or disengaged when overwhelmed

These challenges can affect how autistic people relate to people and places. For example:

- A child may avoid school not because they dislike learning, but because the environment feels overwhelming and anxiety is high.

- An adult may cancel plans or spend time alone, not due to lack of interest, but because constant self-regulation is exhausting.

When these responses are misunderstood by the outside world, such as by caregivers, teachers, peers, or friends, autistic individuals may experience shame, increased anxiety, or a sense of being unsafe und misunderstood.

3. Coping Strategies: What Helps and What Signals Distress

Autistic people often develop coping strategies to manage executive overload. Some strategies support well-being, while others are signs that the person is struggling.

Supportive Coping Strategies

- Visual schedules or written reminders

- Breaking tasks into small, clear steps

- Predictable routines and preparation for change

- Sensory supports such as movement breaks or quiet spaces, noise-cancelling headphones

- Calming and meaningful activities

- Creating a ‘Happy Place’ at home for downregulation after exposure to triggers

- Finding the right balance between time-in (socialising and general exposure to anxiety-evoking stimuli) and time-out (time spent alone/ being in comfort zone)

Coping Strategies That Signal Overwhelm

- Avoidance or withdrawal

- Shutdowns, meltdowns, or emotional outbursts

- Strong rigidity or perfectionism

- Masking or people pleasing that leads to exhaustion

These responses are not chosen deliberately. They are ways of coping when demands exceed available support.

It is especially important for caregivers and teachers to be careful with both positive and negative punishments. Rewarding or punishing behaviour without understanding the underlying stress can increase anxiety, avoidance, and shutdowns. Over time, this can worsen executive functioning difficulties rather than improve them. Encouraging the autistic person to reach out for help is key. With understanding and appropriate adjustments, many autistic people can develop safer and more sustainable ways of coping.

4. How Others Can Offer Helpful Support

Autistic people often experience rigid or inflexible thinking, which is a core autistic trait. This can include a strong need for sameness, difficulty adapting to change, literal interpretations, and what is sometimes described as black-and-white thinking or perseveration. These patterns stem from neurological differences that favour predictability and clarity. When routines are disrupted or expectations are unclear, anxiety can increase quickly.

This rigidity is not intentional and is not a form of defiance. It reflects a need for safety and structure. With the right support, flexibility can be developed over time.

Caregivers can help by:

- Keeping language clear, concrete, and consistent

- Supporting regulation before expecting independence

- Preparing children in advance for changes, using visual aids or written reminders

- Introducing changes gradually rather than all at once

- Using visual schedules, choice boards, or step-by-step plans

- Supporting therapies or approaches that gently build cognitive flexibility

- Paying attention to effort and strengths rather than focusing only on outcomes

- Helping your child set manageable and measurable goals (often called SMART goals in CBT), focusing on very small steps related to self-care and self-sufficiency, such as getting dressed, preparing a simple snack, organising a school bag, or establishing a healthy night routine

Small, achievable steps help build confidence, reduce overwhelm, and support gradual independence.

Teachers and Educational Staff

- Try to find out how the autistic student learns best by also focusing on their emotional and physical challenges

- Allow extra time and flexibility. You need to be more flexible than your neurodivergent student

- Avoid treating executive difficulties as behaviour problems

Friends and Peers

- It’s okay to be different!

- Be clear and direct in communication

- Accept changes or cancellations without judgment.

- Try to find out what your friend likes and dislikes. Remember that what is easy for you might be difficult for them and vice versa.

- Respect sensory and emotional limits.

Across all settings, understanding makes the biggest difference. When autistic people feel understood rather than judged, anxiety often reduces, executive functioning improves, and connection becomes easier.

Final Thoughts

Executive functioning challenges are a common part of the autistic experience. They influence daily life, relationships, and well-being. With the right understanding and support, these challenges can become more manageable.

The goal is not to force autistic people to fit into systems that do not work for them, but to adapt environments, expectations, and support. When this happens, autistic individuals are more likely to feel safe, capable, and connected.

Share on: Twitter, Facebook, WhatsApp, Google+

Published on 2026/01/12

Posted in: Children and Adolescents, Mental Health,